Solar System

The planetary system we are most familiar with is the Solar System, that includes the Sun and all celestial bodies that orbit it. Interestingly, over of the Solar System’s mass is contained in the Sun, which more than justifies the approximations we made when talking about the underlying celestial mechanics of the Solar System. We’ll go through the details of its constituent members in this section.

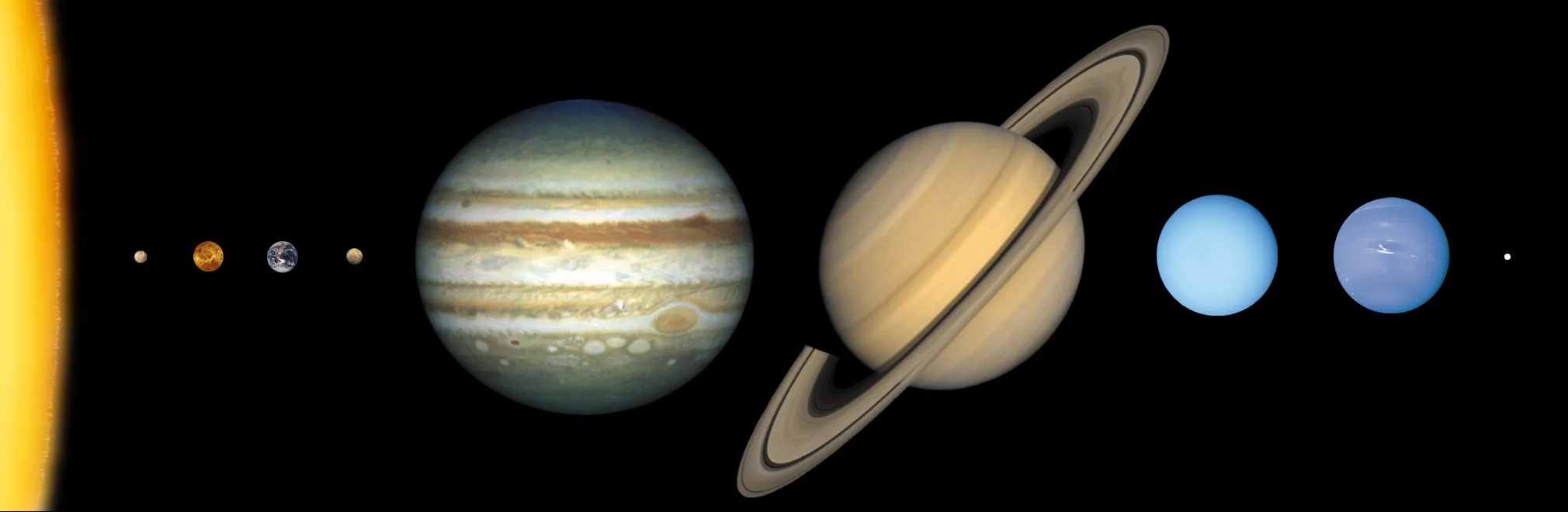

The most massive bodies orbiting the Sun are the eight planets. We divide these into three groups: the four terrestrial planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars), the two gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn), and the two ice giants (Uranus and Neptune).

There are a vast number of less massive objects. The Solar System has five officially recognised (by the IAU) dwarf planets: Ceres, Pluto, Haumea, Makemake, and Eris. Six planets (Mercury and Venus don’t have moons), five dwarf planets, and other bodies have orbiting natural satellites, which are commonly called ‘moons’, and range from sizes of dwarf planets to moonlets.

Furthermore, there are small Solar System bodies, such as asteroids, comets, centaurs, meteoroids, and interplanetary dust clouds. Some of these bodies are in the asteroid belt (between Mars’s and Jupiter’s orbit) and the Kuiper belt (just outside Neptune’s orbit).

Between the bodies of the Solar System is an interplanetary medium of dust and particles. The Solar System is constantly flooded by outflowing charged particles from the solar wind, forming the heliosphere. At around astronomical units (I’ll define this unit in a second, but its about million kilometers) from the Sun, the solar wind is halted by interstellar medium, resulting in the heliopause. This is the boundary to interstellar space. The Solar System extends beyond this boundary with its outermost region, the theorized Oort cloud, the source for long-period comets, extending to a radius of AU (astronomical unit).

The Solar System currently moves through a cloud of interstellar medium called the Local Cloud. The closest star to the Solar System, Proxima Centauri, is light-years ( AU) away. Both are within the Local Bubble, a small region of the Milky Way.

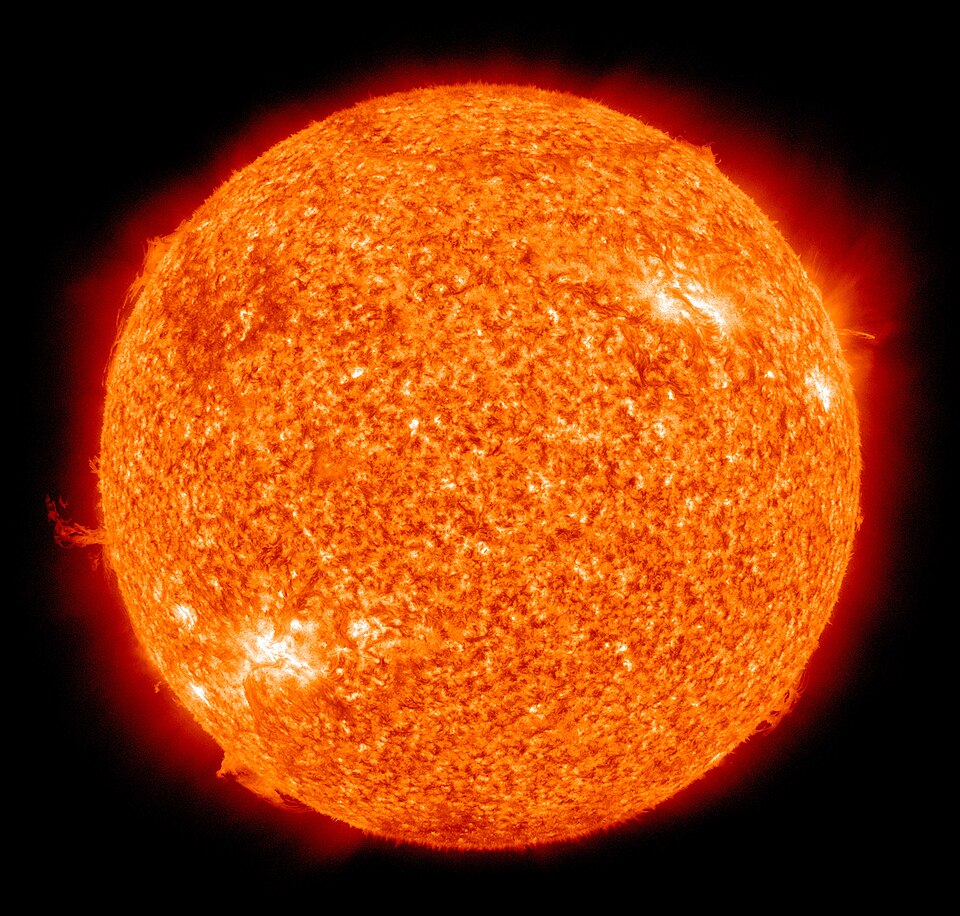

Sun

The Sun is the most important source of energy of life on Earth, as we all know. It is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, with internal convective motion that generates a magnetic field via a dynamo process.

The Sun is composed of about hydrogen, helium, and heavier elements (by mass). It has a diameter of about million kilometers ( miles), which is about times that of Earth, and a mass of approximately kg, which is about times that of Earth. It is at a distance of about million kilometers from Earth (the mean distance between both centers), which is defined to be an astronomical unit (AU).

The Sun is a G-type main-sequence star and is currently in the middle of its life cycle, having formed about billion years ago. It is expected to continue burning hydrogen in its core for another billion years before evolving into a red giant and eventually shedding its outer layers to form a planetary nebula, leaving behind a white dwarf.

The Sun is a Population I star, meaning it has a relatively high metallicity compared to older stars. It is located in the Orion Arm of the Milky Way galaxy, about 26,000 light-years from the galactic center.

The Sun has an absolute magnitude of and an apparent magnitude of about making it the brightest object in the Earth’s sky. Its surface temperature is approximately K, and it emits light primarily in the visible spectrum, with significant amounts of ultraviolet and infrared radiation.

The Sun rotates faster at its equator than at its poles, with a rotation period of about days at the equator and about 35 days at the poles. This variation in rotation contributes to the Sun’s complex magnetic field and the formation of sunspots. Sunspots are temporary phenomena on the Sun’s photosphere that appear as spots darker than the surrounding areas. They are caused by magnetic activity and are cooler than the surrounding regions, with temperatures of about K compared to the photosphere’s K. These tend to occur in pairs or groups of opposite polarity and can last from a few days to several months. The number of sunspots varies over an approximately -year solar cycle, which is associated with changes in the Sun’s magnetic field.

The photosphere is defined as the layer of Sun’s atmosphere from which nearly all the observed photons escape.

The chromosphere is the layer immediately above the photosphere. Bright extended regions in the chromosphere are called spicules, which are jets of plasma that shoot up into the corona. Chromosphere also has dark, linear features called filaments, which are cooler regions of plasma suspended above the photosphere by magnetic fields. When viewed against the Sun’s disk, these filaments appear as dark lines, but when viewed against the background of space, they appear bright.

The corona is the outermost layer of the Sun’s atmosphere, extending millions of kilometers into space and is only visible by the naked eye during a total solar eclipse as a halo of plasma. It contains extremely hot plasma. The outward flow of plasma from the corona is called the solar wind, which carries charged particles away from the Sun and interacts with the Earth’s magnetic field, causing phenomena such as auroras.

A prominence is a large plasma structure extending outward from the Sun’s surface. It is usually anchored to the Sun at the photosphere, and extends into the corona. In contrast to the corona, it usually contains much cooler plasma. Like the corona, they’re also only visible by the naked eye during a total solar eclipse. A prominence that sends matter upwards at speeds greater than the escape velocity is called a coronal mass ejection.

Solar flares are sudden bursts of energy on the Sun’s surface, releasing large amounts of radiation and charged particles. These occur in the chromosphere and the energy released comes from the magnetic field of the Sun. They are often associated with sunspots and can have significant effects on space weather, including disruptions to satellite communications and power grids on Earth.

Earth

The Earth is of course the celestial body we know the most about. It is the third planet from the Sun and the only known astronomical object to harbor life. It is an oblate spheroid (flatter at the poles, so that the diameter at the equator is greater than the pole-pole diameter), with a diameter of about km ( miles) at the equator and about km ( miles) at the poles. The Earth has a mass of approximately kg.

It is primarily composed of iron, oxygen, silicon, magnesium, sulfur, nickel, calcium, and aluminum. The Earth’s atmosphere is composed of nitrogen, oxygen, and trace amounts of other gases such as argon, carbon dioxide, and water vapor.

The Earth has a single natural satellite, which we know as the Moon, which is about km ( miles) in diameter and orbits the Earth at an average distance of about km ( miles). The Moon has a significant effect on the Earth’s tides and stabilizes its axial tilt, which helps maintain a relatively stable climate.

Atmosphere

Earth’s atmosphere is a thin layer of gases that surrounds the planet, held in place by gravity. It extends about 10,000 km (6,200 miles) above the Earth’s surface and is composed of layers, each with distinct characteristics. It is extremely important for the sustainment of life on Earth. It not only affects the climate and temperature of regions, but also protects us from most of the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation.

The troposphere is the lowest layer, extending from the Earth’s surface to about km ( miles) high. It contains about of the atmosphere’s mass and is where weather occurs. The temperature decreases with altitude in this layer.

The stratosphere is above the troposphere, extending from about km ( miles) to about km ( miles) high. It contains the ozone layer, which absorbs and scatters ultraviolet solar radiation. The temperature increases with altitude in this layer due to the absorption of UV radiation by ozone.

The mesosphere is above the stratosphere, extending from about km ( miles) to about km ( miles) high. It is the coldest layer of the atmosphere, with temperatures decreasing with altitude. This layer is where most meteors burn up upon entering the Earth’s atmosphere.

The thermosphere is above the mesosphere, extending from about km ( miles) to about km ( miles) high. It is characterized by a dramatic increase in temperature with altitude, reaching up to °C ( °F) or more. The thermosphere contains a small proportion of the atmosphere’s overall mass and is where the auroras occur.

The exosphere is the outermost layer of the Earth’s atmosphere, extending from about km ( miles) to about km ( miles) high. It is where the atmosphere transitions into outer space and is characterized by extremely low densities of particles. The exosphere is primarily composed of hydrogen and helium, with trace amounts of other gases.

Aside from these layers, the regions with high concentrations of charged particles form the ionosphere, which plays a crucial role in radio communication and GPS systems by reflecting and refracting radio waves. However, the ionosphere is not a distinct layer but rather a region that overlaps with the thermosphere and parts of the mesosphere.

Magnetosphere

Earth has a magnetic dipole field that is generated by convective motions within its molten outer core. The magnetic axis is tilted about 12 about the rotation axis and tends to wobble erratically. The field strength can be roughly approximated as that of a magnetic dipole field:

where is the magnetic field strength at the surface of the Earth, is the magnetic moment, is the distance from the center of the Earth, and is the radius of the Earth. The field strength at the surface of the Earth is about to .

The terrestrial magnetosphere is the region of space around the Earth where the magnetic field dominates the motion of charged particles. It extends several tens of thousands of kilometers into space and is shaped by the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emitted by the Sun.

The terrestrial magnetopause is the boundary between the magnetosphere and the solar wind. It is where the pressure from the solar wind is balanced by the Earth’s magnetic field. The magnetopause is not a fixed boundary; it can move in response to changes in the solar wind and the Earth’s magnetic field.

Some of the particles can partially penetrate Earth’s magnetic field, forming the radiation belts, which are regions of trapped charged particles. The inner radiation belt is primarily composed of high-energy protons and electrons, while the outer radiation belt contains high-energy electrons and some heavier ions. Van-Allen radiation belts are the two main regions of trapped particles in the magnetosphere, named after James Van Allen, who discovered them in 1958.

Moon

The Moon is Earth’s only natural satellite and the fifth-largest moon in the Solar System. It is about km ( miles) in diameter, which is about one-fourth the size of Earth. The Moon has a mass of approximately kg, which is about of Earth’s mass.

It has a very thin atmosphere, called an exosphere, which is composed of trace amounts of hydrogen, helium, neon, and other gases. This exosphere is so thin that it cannot support human life, and the Moon’s surface is exposed to the vacuum of space. It has no significant magnetic field, and its surface is exposed to cosmic radiation and solar wind. The lack of atmosphere means that the temperature on the Moon can vary widely, ranging from about -173 °C at night to about 127 °C during the day (perhaps now you see why an atmosphere is so important!)

The Moon has a synchronous rotation, meaning it rotates on its axis at the same rate that it orbits the Earth. This results in the same side of the Moon always facing the Earth, a phenomenon known as tidal locking. As you might expect, the side of the Moon that faces Earth is called the near side, while the side that faces away is called the far side.

The Moon’s surface is covered in a layer of fine dust and rocky debris called regolith, which is composed of small fragments of rock and mineral grains. The surface is also marked by impact craters, which are formed by the collision of meteoroids and other celestial bodies with the Moon’s surface.

Mares are large, dark plains on the Moon’s surface formed by ancient volcanic activity. They are less cratered than the highlands and are primarily composed of basalt rock. The Moon has no liquid water on its surface, but there is evidence of water ice in permanently shadowed craters at the lunar poles (which by the way, was what the Chandrayan 3 mission was all about). These regions are extremely cold and have not been exposed to sunlight for billions of years, allowing water ice to accumulate.

The Moon has a very weak gravitational field, about th that of Earth’s, which means that objects on the Moon weigh significantly less than they do on Earth. This low gravity allows for unique phenomena such as lunar dust settling slowly and the ability to jump higher than on Earth.

Even though it is quite a bit weaker than Earth’s gravity, due to the relatively small Earth-Moon distance, its gravity has a significant effect on Earth, particularly in relation to ocean tides. The gravitational pull of the Moon causes the oceans to bulge out on the side of the Earth facing the Moon, creating high tides. The rotation of the Earth causes these tidal bulges to move, resulting in two high and two low tides each day. Of course the sun also contributes to the overall tidal patterns on Earth, but its tidal effect is approximately half that of the Moon.

A spring tide occurs when the Sun, Moon, and Earth are aligned, resulting in higher high tides and lower low tides. A neap tide occurs when the Sun and Moon are at right angles to each other, resulting in lower high tides and higher low tides.

Of course everything isn’t so ideal. In open ocean, there is a delay of about 40 minutes between the moon’s transit and the following high tide due to friction between the water and the ocean floor, which slows down the movement of the tidal wave. However, the tidal bulges go around the Earth at the same rate as Moon, once per month. But notably their position is not the same as (along the direction pointing towards) the moon, just the overall time period is. The friction between the tidal bulges and the more rapidly rotating Earth tends to draft bulges forward from where they would otherwise be; forward by about 10 at the equator.

This causes the tidal bulges to be slightly ahead of the Moon, resulting in a gradual slowing of the Earth’s rotation and a corresponding increase in the distance between the Earth and the Moon because the tidal bulge exerts a gravitation force on the moon, causing it to move to a higher orbit (note that if it was not ahead of the moon, the gravitational forces would be along the line connecting the Moon and the Earth, so that it wouldn’t really have an effect). Conversely, because of this, the Moon exerts a force on the tidal bulge, which slows down the rotation of the Earth.

But this effect is very small! Measurements show that the Moon is moving away from the Earth at a rate of about cm per year and Earth’s day is getting longer by milliseconds per century.

Other Planets

The solar system has eight planets which are divided into three groups: the four terrestrial planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars), the two gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn), and the two ice giants (Uranus and Neptune).

Mercury is the closest planet to the Sun and has a thin atmosphere composed mostly of oxygen, sodium, hydrogen, helium, and potassium. It has a heavily cratered surface and experiences extreme temperature variations due to its lack of atmosphere. It has a highly eccentric orbit (orbital eccentricity, not that mercury is particularly weird), taking about Earth days to complete one revolution around the Sun. It has no moons and is the smallest planet in the Solar System. It is in a 3:2 spin-orbit resonance, meaning it rotates three times for every two orbits around the Sun.

Venus is the second planet from the Sun and has a thick atmosphere composed mostly of carbon dioxide, with clouds of sulfuric acid. It has a surface temperature of about °C, making it the hottest planet in the Solar System, even though it is not the closest to the Sun! (Primarily due to its atmosphere). Venus has a retrograde rotation, meaning it rotates in the opposite direction to its orbit around the Sun, taking about Earth days to complete one rotation. It has no moons and is often referred to as Earth’s “sister planet” due to its similar size and composition.

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and has a thin atmosphere composed mostly of carbon dioxide, with traces of nitrogen and argon. It has a reddish appearance due to iron oxide (rust) on its surface. Mars has the largest volcano in the Solar System, Olympus Mons, and the largest canyon, Valles Marineris. It has two small moons, Phobos and Deimos. Both the moons are irregular in shape and are thought to be captured asteroids. Mars has a day length similar to Earth’s, about hours, but its year is about Earth days due to the larger orbit.

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It has a thick atmosphere composed mostly of hydrogen and helium, with traces of methane, ammonia, and water vapor. Jupiter has a strong magnetic field and is known for its Great Red Spot, a giant storm that has been raging for at least 350 years.

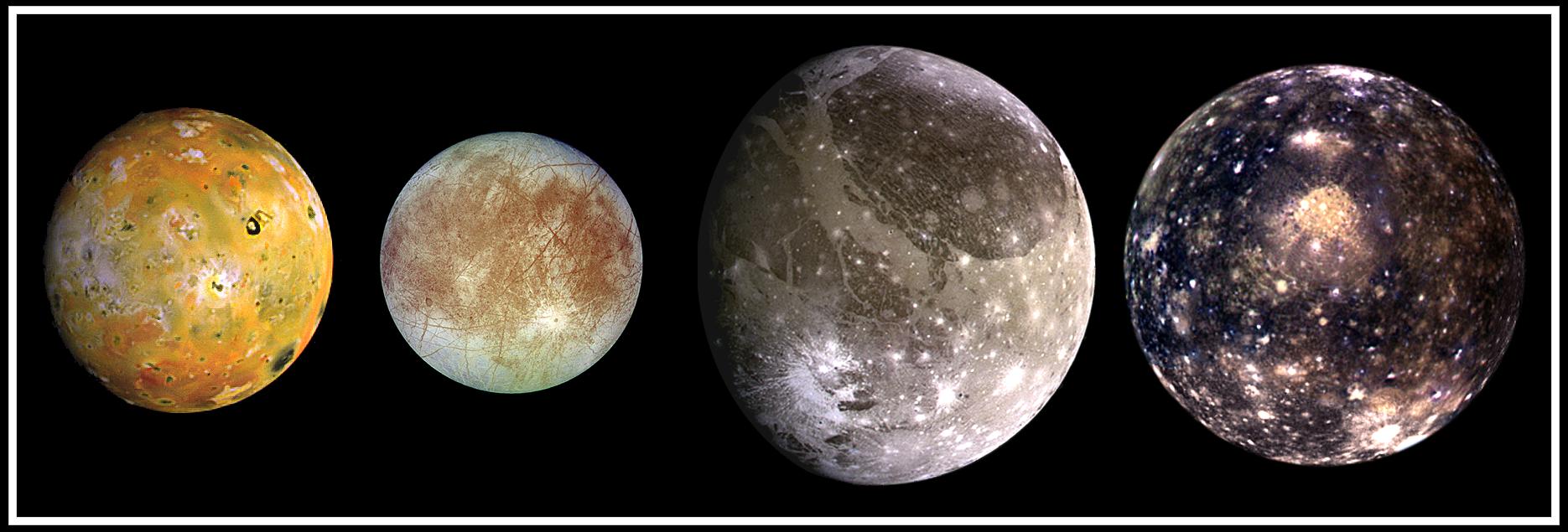

It has at least known moons, including the four largest, known as the Galilean moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Jupiter has a day length of about hours and takes about Earth years to complete one orbit around the Sun.

Io’s surface is covered in active volcanoes, while Europa is believed to have a subsurface ocean beneath its icy crust, making it a candidate for potential extraterrestrial life. Ganymede is the largest moon in the Solar System and has its own magnetic field, while Callisto is heavily cratered and has a thin atmosphere. Io’s main source of heat is tidal heating due to its gravitational interaction with Jupiter and the other Galilean moons.

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and is known for its prominent ring system, which is composed of ice and rock particles. It too has a strong magnetic field, and a thick atmosphere composed mostly of hydrogen and helium, with traces of methane, ammonia, and water vapor. Saturn has at least known moons, with Titan being the largest.

Titan is unique among moons in the Solar System as it has a dense atmosphere and liquid lakes of methane and ethane on its surface. Saturn has a day length of about hours and takes about Earth years to complete one orbit around the Sun.

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun and is an ice giant with a thick atmosphere composed mostly of hydrogen, helium, and methane. It has a faint ring system and is unique in that it rotates on its side, with an axial tilt of about degrees. This means its poles are almost in the plane of its orbit around the Sun. Uranus has at least known moons, with Titania and Oberon being the largest. It has a day length of about hours and takes about Earth years to complete one orbit around the Sun. It has a faint ring system and is unique in that it rotates on its side, with an axial tilt of about degrees.

Neptune is the eighth planet from the Sun and is also an ice giant with a thick atmosphere composed mostly of hydrogen, helium, and methane. It has a faint ring system and is known for its strong winds and storms, including the Great Dark Spot, which was similar to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot. Neptune has at least known moons, with Triton being the largest. Triton is unique among large moons in the Solar System as it has a retrograde orbit, meaning it orbits Neptune in the opposite direction to its rotation. Neptune has a day length of about hours and takes about Earth years to complete one orbit around the Sun.

Dwarf Planets

IAU defines a planet as a celestial body that

- is in orbit around the Sun,

- has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces and assume a nearly round shape (hydrostatic equilibrium),

- has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit

A dwarf planet is one which satisfies the first two conditions, but not the third. The IAU currently recognizes five dwarf planets: Ceres, Pluto, Haumea, Makemake, and Eris. However, we usually refer to nine dwarf planets colloquially: Ceres, Orcus, Pluto, Haumea, Quaoar, Makemake, Gonggong, Eris, and Sedna, because they all just about fit the requirements.

Other Objects

Aside from the main celestial bodies and dwarf planets, there are other objects also present in the solar system. Let’s go through them.

Asteroids are small rocky bodies that orbit the Sun, primarily found in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. They are remnants from the early Solar System and vary in size, shape, and composition. The largest asteroid is Ceres, which is also classified as a dwarf planet.

TNOs (Trans Neptunian Objects) are objects that orbit the Sun beyond the orbit of Neptune. They include a wide range of objects, such as Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs), scattered disk objects, and detached objects. The Kuiper Belt is the region which contains a lot of them, it is a region of the Solar System beyond Neptune’s orbit, populated by small icy bodies, including dwarf planets like Pluto and Haumea.

Asteroids found near the and Lagrange points of Jupiter’s orbit are called Trojan asteroids (based on which we usually call a much lighter, stable, third body in a 3 body system a trojan). They share Jupiter’s orbit around the Sun and are named after characters from Greek mythology.

Comets are icy bodies that originate from the outer regions of the Solar System, such as the Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud. When they approach the Sun, they develop a glowing coma and a tail due to the sublimation of their ices. Comets are classified into two main groups: short-period comets, which have orbits that take less than 200 years to complete, and long-period comets, which have orbits that take more than 200 years.

Finally, meteoroids are small rocky or metallic bodies that travel through space. When they enter the Earth’s atmosphere and burn up, they produce a bright streak of light called a meteor. If a meteoroid survives its passage through the atmosphere and lands on the Earth’s surface, it is called a meteorite.